|

TAKING

THE PESO

Last December, the people of Argentina rose up in fury against

the economic disaster wrought on them by their government, hand

in hand with big business, banks and the International Monetary

Fund (IMF). The world watched on TV as pictures of supermarkets

and food shops being looted showed a country at breaking point.

On the evening of the 19th of December President De la Rúa

appeared on Argentinean TV, refusing to resign and instead imposing

a state of emergency. Within minutes of his broadcast, the people

took to the streets. In Buenos Aires, an estimated million people

left their homes and headed for the main Plaza de Mayo, banging

pots and pans, chanting ‘El estado de sitio, que se lo meten

en el culo’ (the state of emergency, they can stick it up their

arse), and demanding the resignation of De la Rúa and the

whole government. ‘Que se vayan todos!’ (out with them

all!) quickly became the main slogan, and after two days of protest

and repression which left some 35 people dead, President De la Rúa

duly obliged and fled.

Since then, Argentina has been through an astonishing time.TV news

has become a surreal portrait of a country turned upside down –

a Congresswoman’s house is set on fire by a mob outside after

her son shoots a protestor from inside; a group of artists hold

a ‘mierdazo’ – a shit-throwing demo – on the

steps of Congress under the slogan ‘Putting the shit where

it belongs’; farmers bring hundreds of chicks they can’t

afford to feed to the steps of a provincial government house –

when another march, of piqueteros, arrives, they scoop up the chicks

and take them away to eat. Popular assemblies have sprung up in

barrios (neighbourhoods) all over the country, and the unemployed

workers’ movement, the piqueteros (picketers), have stepped

up their road-blocking activities. As these two currents of protest

form tentative links, the loan sharks of the IMF, despised by the

people, are in town again to impose their will on a government desperate

for more ‘assistance’ and still willing to go to any lengths

to get it.

Eyewitness

Account...

An eye-witness account of the uprising of the 19th December,

posted on indymedia

“ I was watching television, seeing the lootings and the uprisings

in the country’s interior. Suddenly the president appeared

on the screen, he was talking about differentiating between criminals

and the needy. He spoke quietly, almost elegantly, trying to sound

in charge. He said he had announced today the state of emergency.

I knew that it is unconstitutional in Argentina for the president

to declare a state of emergency, only the congress can do that.

I was disgusted and I turned off the TV.

I started hearing a sound…a very quiet sound, but growing.

I went to the balcony of my apartment and looked out - people on

every balcony banging pots and pans. The sound got louder and louder…

it was a roar, and it wasn’t going to stop. I saw some people

on the corner of the street I live, no more than 10. I put on a

shirt and went down. On every corner I could see people gathering

in small groups. This is a comfortable middle class neighbourhood,

but everybody’s been fucked by what’s going on, and it’s

been going on for far too long. On the corner of the next street

people had started gathering on the middle of the streets. Banging

spoons against pans, waving flags…in a few minutes we were

something like 150 people.

We started walking. Nobody seemed to know where we were going or

what was gonna happen…an hour had gone by since the banging

started and the noise wasn’t stopping, coming from every corner

of the city. As we walked, people were joining us, it was exciting,

almost manic. The feeling of regaining your own power. I looked

back and suddenly this spontaneous demonstration was a couple of

blocks long. I could see people in suits and people in working uniforms.

I could see young girls in nice clothes and senior citizens in old

clothes. I could see the small businessman who is suffering from

higher and higher taxes and it’s about to lose his house from

his bank loans and the young man who has been excluded by the system

and couldn’t get a job for 4 years. Everybody was represented.

It was amazing. People cheered from the balconies, small pieces

of shredded paper falling slowly to the streets…singing, banging,

marching.

When I got to Congress, a couple of thousand people were already

there and I could see more people coming in from every corner. It

felt like a party. The flags waving, the chants, the clapping. A

guy at the top of the steps lit some sort of smoke-flare - pink

smoke all over the place. I looked around, I don’t know why

but I started feeling tense. People kept on coming and we started

marching to the Casa Rosada. Things didn’t feel exciting anymore,

it felt tenser and tenser. I could see some fire on the street ahead

- a small trashcan on fire. I kept on walking. Some people were

quietly singing and clapping but I saw other small fires. I had

entered a column that came from a tougher neighbourhood than mine.

I don’t blame them - they’ve been fucked way harder than

anybody else and hunger breeds anger. A young guy was banging a

stick against a street sign, and this thirtyish guy, skinny and

dressed in really old jeans and shirt, holding a young girl in his

arms, said something to him. The young man looked back, he saw the

columns of people. I could catch this phrase from the skinny guy

“Look at how many we are”. I looked back. I saw and felt

what I felt at the beginning. Everybody was there, everybody was

represented, we were so many.

When I got to Plaza de Mayo a couple of thousand were there and

they kept on coming. People started coming in on cars as well as

marching. Young people, old people, families - the people. I walked

around. Amazed. I was thinking that not many days you go to the

balcony to check the noises coming from the streets and you end

up being a witness to a presidential deposal by social uprising.

Suddenly I was pushed in the back by somebody. When I regained balance

I saw people running away. Somebody was yelling “Sons of bitches”

right next to me. Out of instinct I started running with them. I

ran half a block, stopped and looked back. I saw thousands of people

running.

Somebody passing me said something about the police. I couldn’t

quite understand…my nose started itching. I looked back - in

the plaza, 500 metres back, I could see smoke. People’s eyes,

they were reddening. My throat hurt. I ran. People were going off

in all directions away from the plaza. The smoke got higher and

higher, I took off my shirt and covered my nose and mouth. My eyes

itched. I got pretty far and looked around. This guy in a Miami

Florida T-shirt, absolutely middle class, said he now understood

what the piqueteros felt. I suddenly realized I was crying. I didn’t

know if it was from the tear gases or from impotence and anger.

* Serious street fighting followed, that night and the next day,

and 35 people were killed during the two-day insurrection; 5 were

shot dead by police in and near the Plaza de Mayo, and many others

were killed by police and shop-keepers during lootings.

REBEL ALLIANCE - Wed 17th April @ Hobgoblin, Brighton 7PM

Que Se Vayan Todos (out with all politicians)

The following is a condensed version of eye-witness reports

sent to Schnews from Buenos Aires in January.

Fri, 18 Jan 2002

The streets are emptier in Buenos Aires at night, than I have ever

seen them. In the centre of the city in the daytime it’s as

crowded as ever. Queues for exchange bureaux stretch around blocks.

There’s a feeling in the air of anxiety and barely-surpressed

anger. Walking down the main pedestrian avenue, Florida, I heard

a woman laugh too loud, and everyone jumped and shot her alarmed

stares. ‘Ladrones usureros’ - usurers, thieves is scratched

onto the marble plaque outside the Bank of Boston. The Lloyds and

HSBC banks have put up enormous metal panels over their windows;

in the provinces, banks are being ransacked every day. The TV news

shows protest after protest; today in Santiago del Estero, in the

North, there are barricades in the streets and brutal police repression

of the mostly middle-aged working men who are demanding ‘Dignidad

para el obrero’ - dignity for the workers. In La Quiaca, ,

people are crucifying themselves every day, 5 hours each in the

hot sun, while the children hold signs saying ‘pan y trabajo’

(bread and work) and ‘luchamos contra el hambre’ (our

struggle is against hunger). Yesterday, after a cacerolazo outside

the Supreme Court to demand the resignation of its 9 judges, the

people went to the home of one of the judges and continued there.

Politicians and judges can’t walk the streets in case they

are recognized - a friend was queuing at a bank the other day when

a judge drew up in a car and tried to go in. Everyone started abusing

him - ‘ratta!’ (rat), ‘corrupto’, ‘hijo

de mil putas’ (son of a thousand whores), until he took refuge

in his car and left.

Peoples’ fury at their inability to access their savings, due

to banking restrictions, is worsened by news of 386 trucks stuffed

with cash, which ferried an estimated 26 billion dollars to the

airport after banking restrictions had been imposed, for transfer

to Uruguay and beyond. Given the numerous stories of massive ‘capital

flight’ over the early days of this crisis, and of businesses

and banks which mysteriously took out fortunes before and during

the strict new measures, people think most of their money will never

be seen again. There are many for whom the corralito means nothing

– they have nothing in the bank. Unemployment is over 20%,

and there is hunger in many areas. Pensioners are badly affected.

They have had no pensions since November - millions of workers are

going unpaid. The state medical system, PAMI, has collapsed due

to lack of funds. There is an extreme shortage of insulin and other

common drugs, because they are imported and because many drugs were

withdrawn from the shelves by pharmaceutical companies, to protect

prices. In the outlying, poorest barrios people have arms and use

them, but actual robberies are outstripped by paranoia and vigillanteeism,

born of government disinformation about supposed widespread looting

of homes. Many people are trying to leave the country, reluctantly

but seeing no future in Argentina - when it was reported this week

that Poland was to join the EU, a queue formed immediately at the

Polish embassy. Thousands of the large Chilean population of Mendoza

have gone home, as have many of the Bolivian, Peruvian and Paraguayan

migrant workers. People talk bitterly of institutional corruption

from top to bottom. Now, as well as blaming the IMF, the free market

economy forced on them by Menem (the whole-sale selling off and

privatisation), and the constant flight of capital abroad, people

are beginning to blame themselves. It’s bitter and humiliating.

Mon, 21 Jan 2002

Yesterday we went to the general assembly, the ‘Interbarrial’,

of the almost 100 neighbourhood (‘barrio’) assemblies

of Bs. As. in Parque Centenario, and attended by about 2,000 people.

There were speeches from each barrio, telling of their experiences,

listing actions they planned and putting forward proposals. There

was a lot of talk about the Supreme Court and continuing the protests

against it until all the judges resigned - or to go in and boot

them out themselves. The media was denounced by many speakers for

its lies and distortion; meanwhile, the news that there were TV

crews from Japan, Spain, UK and Finland present at the assembly

was greeted with cheers, while the mention of a US TV crew met with

angry whistles and boos. There were no Argentinian TV crews present

at all. Speakers suggested that anyone who had held a political

post in the last 30 years should be disqualified from ever doing

so again. They denounced the new budget and banking reforms due

to be announced this week as measures that were bound to suit the

‘yanquis’ (USA) - the new economy minister is a veteran

of 20 years’ service to the IMF. It was agreed that the visitors

from the IMF due here on Tuesday should be greeted with a ‘cacerolazo’.

A speaker proposed that ‘we stay in the streets till they have

all gone’ and commented on the importance of showing that it’s

not just the corralito they are against; that they want to change

it all. There was a minute’s applause for those who died during

the repression which followed the first cacerolazos of the 19th

and 20th of December and chants of ‘Policía Federál,

la verguenza nacionál’ - the Federal Police, a national

disgrace. Barrio after barrio made its proposals, and when the voting

through of the main proposals went ahead they were:

- Que se vayan todos (that all politicians should go)

- No to payment of the external debt

- Justice and punishment for the murderers and repressors

- Nationalisation of the bank and the privatised companies

- The Supreme Court - out!

- Return the money to depositors.

Tue, 29 Jan 2002

On Friday night, the 25th January, a national ‘cacerolazo’,

agreed at the assembly, began at 8pm with the sound of pans clanging

from balconies and in the streets and parks of the capital. By 10pm,

the enormous Plaza de Mayo was starting to fill and the noise was

already deafening,. Along the Av. de Mayo a steady stream of people

was pouring into the square; ‘asambleas barriales’ (neighbourhood

assemblies) arriving from the barrios, hundreds of families and

thousands of old people. The rain was coming on and off in the heat,

but everyone acted like they hadn’t noticed as the square filled

with banging, chanting people. Over the rhythm of beaten pans, chants

were constantly breaking out; the favourite chant, sung by nearly

20,000, football-style: ‘Que se vayan todos, que no quede ni

uno solo’ (that they all go, that not a single one remains).

And, jumping and pointing at the President’s Casa Rosada, cut

off from the square by fencing and lines of stony-faced cops, ‘A

minute’s silence for Duhalde, who is dead’. I look at

the faces of the police behind the fence and I think I see fear

and shame; later, I reconsider.

By 11:30pm the rain is pouring down in buckets, but the crowd only

bangs the pots harder and jumps faster, chanting louder, ‘Que

llueve, que llueve, que el pueblo ne se mueve’ (let it rain,

let it rain, the people are staying here). And suddenly, unexpectedly,

almost on the stroke of midnight, the ‘represión’

begins. Motorcycle police appear and begin to fire teargas and rubber

bullets, causing panicked running here and there; as people on their

way home along the Avenida de Mayo approach the wide Avenida 9 de

Julio, a line of cops appears and fires teargas and rubber bullets

from the front and from side-streets. In the Plaza, people taking

shelter from the rain in front of the cathedral are fired upon with

gas and rubber bullets. The demonstration had been noisy but entirely

peaceful - on TV reports, there is just a single image of a youth

throwing a molotov cocktail at lines of police who have already

emptied the square. It is an incomprehensible response in already

volatile times. I hear a report on the radio of a woman of 70, on

the ground badly wounded, her legs full of rubber bullets, and a

young man with two in his head. Back home, we watch on TV as 20

people, under arrest, are forced to lie face down in the rain with

their hands above their heads - ‘It’s just like during

the dictatorship’, someone says. There are still 300 demonstrators

at Congress, completely surrounded by police. They are chanting

and jumping - ‘El que no salta es policía’ (whoever’s

not jumping is police). We see three young men with their arms over

their heads being thrust towards a police bus. Their t-shirts are

pulled over their heads from the back by police and at least one

is bleeding heavily from the head. A policeman in soaked t-shirt

and shorts is directing uniformed officers as they hustle the lads

onto the bus. In the bar someone says - ‘These sons-of-bitches

haven’t even been paid’ (thousands of people have gone

unpaid, some for months). ‘No importa’, says someone else

‘- lo hacen de onda’. (They don’t mind - they do

it for fun).

PS. This morning, tho’ some of the press made the point that

the demo had been entirely peaceful and the police action unprovoked,

most of the TV news, as always, reverted to type and lied. As graffiti

here in the barrio where we are staying says, ‘Nos mean y la

prensa dice q’ llueve’ (they piss on us and the press

says it’s raining).

Payback

Time

Last year, as the country slipped into total crisis and it looked

likely it was going to default on its eternal (sic) debt, IMF conditions

dictated that the government should make massive cuts in public

spending. State workers’ salaries were cut by 13%, as were

state pensions, in yet another round of austerity measures which

helped to push people’s patience right to its limit. Argentina

has paid and paid for its addiction to IMF ‘assistance’,

and it looks as if it will be paying for years, in ways it never

thought possible. The deployment of Argentinean troops to the Gulf

War and to Bosnia are examples of favours called in by the USA,

as is the training of Colombian airforce pilots in Argentina. US

and Latin American troops, commanded and financed in Washington,

have carried out exercises in Argentina without Congress’s

approval, and despite this being in violation of Argentina’s

constitution.

Argentina is about to vote, for the third time, against Cuba’s

human rights record at the UN, this time as a proposer of the motion.

It has promised Washington to ‘work for the liberty of the

Cuban people,’ to the disgust of the Argentinean people and

Fidel Castro, who has yet again called the government ‘yankee

boot-lickers’. Another member of the Cuban government expressed

sympathy for Argentina, locked in to ‘carnal relations’

with the USA, for the way the USA is ‘humiliating and pressurizing’

Argentina while denying it the funds to resolve the situation imposed

by ‘the dogmatic imposition of the neo-liberal model’.

And there’s more to come for Argentina. On January 12th, the

New York Times reported US Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld,

as saying the US might be willing to financially assist the Argentinean

government, if they were permitted to install military bases in

Tierra del Fuego, the southernmost tip of the Americas. The governor

of the province has secretly authorised bases, where the US will

be allowed to detonate underground atomic bombs – but only

for ‘peaceful ends’. So that’s alright then.

Silver

Tongued

Buneos Aires - once known as ‘the Paris of Latin America’

has now sunk - along with the rest of Argentina, into what has been

called Latin Americanisation. “It used to be the jewel in the

crown, but now has all the same problems of poverty as the rest

of the continent.” So who’s made us cry for Argentina?

International Monetary Fund, come on down.

Argentina has for the past two and a half decades been the IMF’s

star pupil. It sold off everything, down to its “grandma’s

jewels,” with foreign firms taking over key sectors of the

economy and the utilities. Companies like French multinational Vivendi

Universal, which in 1995 bought most of the water system before

sacking staff and raising prices, up 400 % in some areas. Or the

Spanish oil company Repsol, which snapped up the state-owned YPF,

sacked thousands of workers and turned the only oil company in the

world not making a profit, into a money-spinner estimated to have

taken $60 billion out of the country. Or the Spanish Telefónica,

which bought up most of the privatised telephone system for a bargain

basement price, then whacked up the prices to way above those paid

anywhere else in the world and made a tidy profit of $2 billion

in its first year.

Argentina obediently deregulated its markets and tried to make

its workforce more ‘flexible’ (meaning you work longer

for less pay.) It has jumped through all the IMF hoops, with promises

of prosperity at the end of them, yet now finds itself with a $150

billion dollar foreign debt, with 30% of its GDP going every year

to pay off interest payments alone before December, and is still

paying part of it despite having defaulted.

Loan

Sharks

The first IMF loans were to the military junta in 1976 and since

then, this ‘debt’ has been paid off by the Argentinean

people many times over – and not just in pesos. Argentineans

used to call their country the bread-basket of the world, and say

that in a country bursting with natural resources and a huge agricultural

sector, nobody ever went hungry. But now 40% of the people live

below the poverty line and up to a hundred die every day from poverty-related

illness, with food parcels and medicines now arriving from Spain

and neighbouring Brazil.

In a ruling two years, ago a federal judge summed it up. “Since

1976 our country has been put under the rule of foreign creditors

and under the supervision of the IMF by means of a vulgar and offensive

economic policy that forced Argentina down on its knees in order

to benefit national and foreign private firms.”

Despite the economy being in free-fall, two documents leaked to

investigative journalist Greg Palast show that, for the deluded

economists at the IMF, what the country really needed to get it

back on its feet was even more structural adjustment! So it’s

more cuts for state pensions, salaries, unemployment benefits, education

and health, all of this ensuring that the burden of this so called

‘adjustment’ falls, as ever, on those who can least afford

it.

Anoop Singh, leader of the IMF delegation currently in the country,

admitted it was “the worst economic crisis any country has

had.” Then promptly listed a new set of demands Argentina must

implement immediately before they even get to see how much ‘aid’

they’ll receive. In a veiled threat he commented, “without

an IMF agreement, it will be very difficult for Argentina to recover.”

Since 1983 there have been nine IMF stabilisation plans in Argentina,

‘helping’ the country out.

But it’s not just the IMF that wants more adjustment. Other

financial institutions are still licking their loan shark lips,

saying Argentina’s crisis should not be seen as an obstacle

but as an opportunity because, the reasoning goes, the country is

so desperate for cash it will do whatever the IMF wants. “During

a crisis is when . . . Congress is most receptive,” explained

Winston Fritsch, chairman of Dresdner Bank AG’s Brazil. Meanwhile,

a couple of Massachusetts Institute of Technology economists writing

in the Financial Times, go even further. “It’s time to

get radical…(Argentina) must temporarily surrender its sovereignty

on all financial issues . . . and give up much of its monetary,

fiscal, regulatory and asset-management sovereignty for an extended

period, say five years.”

When Greg Palast interviewed the former chief economist, Joe Stiglitz

- fired by the World Bank for questioning its economic wisdom –

Stiglitz told him about ‘IMF riots’ “Everywhere we

go, every country we end up meddling in, we destroy their economy

and they end up in flames.” He went on to tell Palast that

the IMF even plan for riots, because as the people revolt, capital

drains out of the country (helped by IMF inspired abolition of currency

controls) and whoever’s left in charge has to go begging back

to the IMF for more money. They don’t mind handing some out,

as long as the country agrees to even more demands, and they turn

a blind eye as politicians fill their pockets in return for their

compliance.

On Tuesday the IMF did just that, agreeing to give Argentina $5

billion of its promised, frozen $22 billion loan programme. And

where will that money go? To where it’s really needed –

paying the interest on the debt. The debt gets bigger, the cuts

get harsher – and the money doesn’t even have to leave

Washington. The people of Argentina know the IMF aren’t there

to help them. The only people the IMF dish out their dollars to

are those who in their view really need it; the banks and big business,

the rich and the powerful. For them, the Argentina experiment has

been a stunning success – Shame about the people though, eh?

* Greg Palast’s ‘The Best Democracy Money Can Buy’

(Pluto Press, 2002) www.gregpalast.com

* www.corpwatch.org

* www.50years.org

Money For Sale

The banking restrictions, known as the corralito (meaning the corralling

or ring-fencing of bank deposits), was imposed at the beginning

of December, when nervous savers, feeling disaster approach, started

to withdraw their money from the banks. Since then, its rules have

changed almost daily, allowing a certain amount to be withdrawn

each month, but also forcibly converting most savings, 80% of which

had been deposited in dollars for security (!) into pesos at extremely

unfavourable rates. Those who insisted on keeping their deposits

- which exist on paper only now as the money is no longer in the

country - in dollars, have been forced to accept bonds which may

or may not be repaid in the next year or so, and almost certainly

not in dollars. And those with pesos can only watch as the peso

falls from one-to-one with the dollar, where it had been artificially

pegged for eleven years, to a low of 4 a few weeks ago. The hated

Supreme Court, in a manoeuvre calculated to save its own skin from

moves in Congress to impeach them and from the angry threats of

the people to go in and kick them out, decreed the corralito unconstitutional

on the 1st of February. Some savers laid down their pots and pans

to queue at the court for individual court orders to their banks

to return their deposits, but banks have generally ignored these.

Those with a lot of money or influence routinely skip out of the

corralito with their money, either on the nod from their banks or

through clever dealings with shares in Argentinean companies on

the New York stock exchange.

It’s a different story for businesses, which have been generously

compensated by the (bankrupt) state for the peso-fication of their

debts in dollars. Plans for the peso-fication, at one-to-one despite

the plummeting peso, of debts contracted in dollars was intended

to help individuals with debts like mortgages, who could never dream

of repaying them in the devalued peso, and was going to apply only

to debts of less than $100,000. But an investigation by reporters

on the TV news show ‘Telenoche Investiga’, who were all

sacked and their programme never broadcast, uncovered the truth

about how the debts of big business came to be included in the rescue

plan. On the 12th January, heads of large Argentinean corporations

held a secret meeting with President Duhalde and three other members

of the cabinet. They were told by the president that it might be

possible for their massive debts to also benefit from conversion

at one to one, if they were willing to make a ‘contribution’.

Even the millionaire CEOs were taken aback at the size of the bribe

he was soliciting – it was to be $500 million dollars, in dollars

and in cash. The reporter was told that the money was to be divided

between members of Congress and the Senate ($200 million) who would

have to approve it, $175 million for Mendiguren, Lenicov and Capitanich,

the cabinet members present that day, and a tidy $125 million for

Duhalde. One empresario refused and is now under investigation by

the DGI (General Tax Direcorate). The overall saving to businesses

is estimated to be in the region of $20-30 billion dollars (YPF-Repsol

oil, for example, has been able to halve its $310 million debt);

the money will have to come from more cuts in public spending.

Bourgeois

Block

An email to Schnews describes bizarre scenes as the ‘bourgeois

block’, gangs of enraged savers denied access to their money,

strikes again:

“Tearing off the metal cladding, they invaded the bank lobbies

and in full sight of the police, without a mask or black hoody to

be seen, proceeded to destroy the cash machines. Women with perms,

golden bracelets and high heels kicked at the windows, lipstick

grins spreading as they watched the glass shatter. Every armoured

security van the mob of 300 people came across was surrounded. Men

in business suits proceeded to unscrew the wheel-nuts, while others

prised open the bonnets, tearing out wires from the engines. Soccer

mums jumped up and down on top of vans, smashing anything that could

be broken, wing-mirrors, lights, number plates...”

The former middle class are 'avit it on the street - pissed off

with the banks cos they've lost their money.

PIQUETE

Y CACEROLA, LA LUCHA ES UNA SOLA

The two biggest types of organised resistance in Argentina are

the popular assemblies and the piqueteros, the unemployed workers’

movement which takes its name (picketers) from their trademark tactic

of blocking roads.

The

Piqueteros

Rising unemployment in Argentina over the last few years has created

the world’s largest concentration of unemployed industrial

workers. Many piqueteros are experienced workplace and union activists.

They use the tactic of blocking roads as a way of disrupting production,

setting up camp right on the asphalt, putting up tents and cooking

food. Women and children are a fundamental part of the movement,

and always present. The piqueteros have stepped up their activities

in the last few months, paralysing the capital a number of times,

most recently when the latest IMF delegation arrived to ‘negotiate’.

In February they blockaded oil refineries and depots throughout

the country, demanding 50,000 jobs; new, shorter shifts to employ

more workers; no petrol price rises and the re-nationalisation of

the oil industry and all the privatised companies. They also usually

demand food packages, the release of political prisoners, unemployment

benefits and ‘work plans’ – a type of workfare scheme

worth a meagre 120 pesos a month. An email which arrived at Schnews

last week from a British activist in Buenos Aires:

“There’s loads of different piquetero organisations,

and a lot of divisions, partly caused by old left parties. The CCC

is the largest, and the most reformist [despite the name –

Classist and Combative Current] - they are the ones who concentrate

on demands for proper social security payments. Far more militant

are independent organisations such as CTA Anibal Verón, and

Movimiento Teresa Rodrigues (both named after piqueteros murdered

by cops during blockades), and the MTD (Unemployed Workers Movement).

They see their struggle as a Latin American one, and identify with

the anti-capitalist movement. They are active, highly politicised

people, and probably number 10,000.”

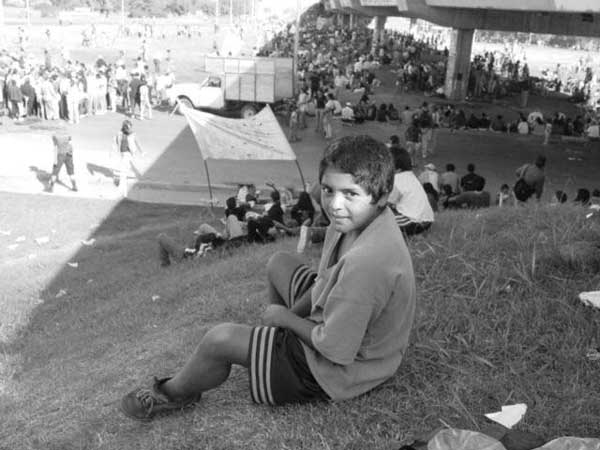

Highway blockaded by the 'piqueteros' on outskirts of Buenos

Aires

Repression

Despite the unprecedented changes happening at street level, there’s

little new in mainstream politics and government. President Duhalde

is an old political hand, and well known for corruption during his

previous years in office. In his nine years as governor of Buenos

Aires, he amassed support, contacts and experience that now stand

him in good stead, including the use of violent thugs (‘patoteros’),

both paid and party political. At his swearing-in as president,

hundreds of his supporters, said to have been paid to come, battled

outside and inside Congress with protestors, and there are even

rumours that some of the looters who precipitated the downfall of

President De la Rúa were paid by the Peronist party. Duhalde

has ordered the repression of at least one cacerolazo, on the 25th

January, since taking power, and is now making use of the thugs

of his party apparatus (officially called the Justicialist Party,

aka Peronism) to intimidate a population which still clearly remembers

the fearsome repression, torture and murder of the military dictatorship

(1976-1983), when 30,000 people ‘disappeared’. In the

Buenos Aires barrio of Merlo a few weeks ago, the assembly was attacked

one assembly has even been shot at. In the barrio of Avellaneda

last Sunday the assembly, gathered to protest at corruption in the

local administration, was prevented from reaching their destination

by a gang of 300 thugs sent by the local municipal leader. Last

Tuesday during one of the regular savers’ protests at the Bank

of Boston, a woman was beaten to the ground, kicked and handcuffed

and had teargas sprayed in her eyes by police, and many of the other

protestors were beaten and arrested.

Popular

Assemblies

Popular assemblies, also known as neighbourhood (barrio) assemblies,

have mushroomed in Argentina since December. A recent survey by

the newspaper Página 12 found that 33% of those questioned

in the capital had participated in them. Assemblies are held on

street corners or public spaces, and operate in the most transparent

way, with what they call a ‘horizontal’ structure and

no leaders or representatives. Born of the first cacerolazos, and

the fertile coming together of neighbours on the streets in protest,

the assemblies discuss and vote on issues ranging from non-payment

of the external debt to the defence of local families in danger

of eviction for non-payment of rent. They have organised collective

food-buying, soup kitchens, support for local hospitals and schools

and even alternative forms of healthcare. Every Sunday, all the

Buenos Aires assemblies meet in Parque Centenario for the Interbarrial

– the inter-neighbourhood mass assembly. Certain sections of

mainstream politics are attempting to participate in or co-opt the

assemblies - like one proposal made in Congress that the assemblies

be given their own space and resources at the Congress building

- but these proposals were vehemently rejected. Pressure from left-wing

parties such as the Partido Obrero (workers’ party), has been

harder to resist. At an Interbarrial in Centenario, a motion was

put that “the party militants stop coming along to assemblies

to lay down party lines - that they take the assembly’s position

back to their parties instead.” The sovereignty of each local

assembly has been reiterated again and again at the Interbarrial

and motions voted there, based on proposals from each assembly,

are taken back to local assemblies to be ratified. Despite this,

a controversial proposal for a Constituent Assembly – an assembly

of delegates - which many felt was an unacceptable move back towards

representative politics, was voted through at the Interbarrial of

March 17th.

Despite their differences, an important similarity is that both

organise outside the sphere of work. The assemblies’ refusal

to negotiate with the government, under the slogan ‘Que se

vayan todos’ – out with all politicians – clashed

with some sections of the piqueteros. Since the economy collapsed

at the end of last year, the total of Argentineans living in poverty

has risen to some 14 million (pop. 36 million), and the middle class

has been destroyed. The piqueteros’ struggle has been going

on for years with little support from the wider public; those who

participate in the cacerolazos and at bank protests are accused

of having acted only when their own pockets were finally rifled.

Despite these contradictions everyone sees the need to link their

struggles together; and many of the piqueteros’ demands, which

seemed radical just a few months ago (non-payment of the national

debt, for example) have become the battle cries of the newly-impoverished

middle class too. On the 27th February, a march of some 5,000 piqueteros

from the poor Buenos Aires suburb of La Matanza was met by a number

of local assemblies, who provided breakfasts and then joined the

march to the Plaza de Mayo. The piqueteros were also cheered along

the route by the people of Buenos Aires, who gave out food and drink

with some even banging their pots and pans. A new slogan was born

– ‘Piquete y cacerola, la lucha es una sola’ (pickets

and pot-bangers, the struggle is one). Piquetero demands include

things like the return of savers’ deposits, while motions at

popular assemblies almost always include support for the piqueteros,

and for occupied factories under workers’ control.

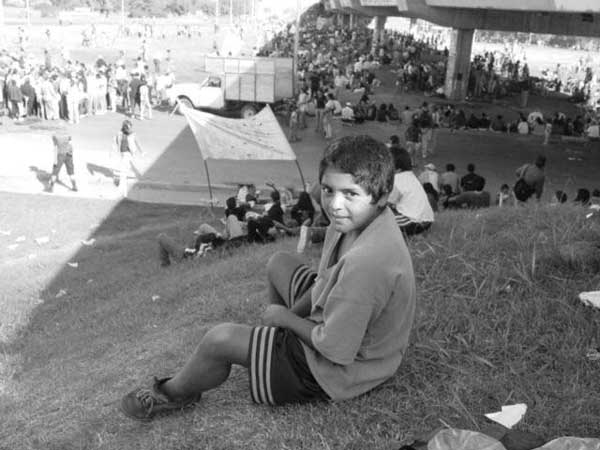

A proposal is voted through at the 'interbarrial' assembly in

[Parque Centenario] Buenos Aires.

Check

Out...

www.argentinaarde.org.ar

(should be online soon)

www.buenosairesherald.com

(English language daily newspaper)

http://.argentina.linefeed.org

(indymedia Argentina, almost all in Spanish)

www.rebelion.org (in Spanish)

http://usuarios.lycos.es/pimientanegra/index.htm

(Mexican site, in Spanish)

www.data54.com (excellent Argentinean

current affairs magazine, in Spanish)

www.zmag.org/argentina_watch.htm

And

Finally...

From the first night of the uprising, the Argentinian people have

shown utter contempt for politicians, summed up in the slogan ‘Que

se vayan todos’ – out with all politicians. Not that this

disillusionment with representative politics is new. In last Octobers

general elections, more than 40% of the (compulsory) votes were

blank or spoiled - the majority going to a cartoon character, Clemente

the cat politician, who has no hands so he cannot steal! So while

politicians in the West denounce their own demonstrators as either

foolish, indulgent or violent for having the cheek to fight for

a better world, the mass media focuses on protests in Seattle and

Genoa, while burying news of general strikes and mass protests in

countries like Argentina. But we know that it will only be people

around the world working together and linking up with international

struggles, that can defeat capitalism. As one of the speakers at

last year’s National Assembly of piqueteros, put it, “Argentina

is part of a world-wide crisis – all over the world piqueteros

are arising. And last week, 300,000 piqueteros invaded the city

of Genoa to say ‘no’ to world-wide imperialism.”

Others have taken up the slogan ‘Todos Somos Argentinos’

– ‘We Are All Argentineans’ –because people

know that what is happening now in Argentina will be happening in

a country near you soon if the IMF and their big business mates

carry on destroying the planet in their never ending search for

profit. Unless of course, we stop ‘em.

Disclaimer

SchNEWS warns all readers we’re ‘avin’ a week

off then back again with more beefy stories - unless we break our

little toe. Honest.

Cor-blimley-they’re-practically-giving-them-away

book offer

SchNEWS Round

issues 51 - 100 £4.50 inc. postage.

SchNEWS Annual issues 101 - 150 £4.50 inc. postage.

SchNEWS Survival Guide issues 151 - 200 and a whole lot more £5.50

inc. postage

The SchQUALL book at only £7 + £1.50 p&p. (US Postage

£4.00 for individual books, £13 for all four).

SchNEWS and SQUALL’s YEARBOOK 2001. 300 pages of adventures

from the direct action frontline. £7 + £1.50 p&p.

You can order the book from a bookshop or your library, quote the

ISBN 09529748 4 3.

In the UK you can get 2, 3, 4 & 5 for £20 inc. postage.

In addition

to 50 issues of SchNEWS, each book contains articles, photos, cartoons,

subverts, a “yellow pages” list of contacts, comedy etc.

All the above books are available from the Brighton Peace Centre,

saving postage yer tight gits.

Subscribe

to SchNEWS: Send 1st Class stamps (e.g. 10 for next 9 issues)

or donations (payable to Justice?). Or £15 for a year's subscription,

or the SchNEWS supporter's rate, £1 a week. Ask for "originals"

if you plan to copy and distribute. SchNEWS is post-free to prisoners.

You can also pick SchNEWS up at the Brighton Peace and Environment

Centre at 43 Gardner Street, Brighton.

|